Four Inquiry Qualities At The Heart of Student-Centered Teaching

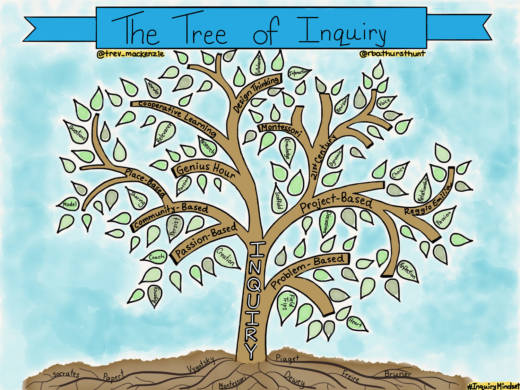

The "Tree of Inquiry" can be a helpful visual to understand how various educational buzzwords connect to inquiry. (Courtesy Trevor MacKenzie and Rebecca Bathurst-Hunt)

By Trevor MacKenzie

Whether it be project-based learning, design thinking or genius hour, it's easy to get confused by the many education buzzwords floating about. But at their heart these pedagogies are all student-centered and there are commonalities across them that are the key to their success and far more critical than keeping the jargon straight.

Naturally, educators want to understand each of these frameworks in order to make an informed decision as to how to best meet the needs of their students. The "Tree of Inquiry" is a visual guide for educators who are interested in shifting their practice but are unsure where to begin. Inquiry-based learning is the foundation for all of these student-centered strategies -- students are asking their own questions, discovering answers and using their teachers as resources and guides. Schools and classrooms where deep inquiry is clearly at work invariably possess four specific characteristics no matter the specific type of inquiry utilized.

1. The learner is actively involved in the construction of understanding

In all of these frameworks, the role of the student is transformed from a passive consumer of facts and content into an active contributor to the learning experience and the exploration of problems, ideas and solutions. It is in this experience that understanding is constructed and rich learning occurs. Voice and choice are at the heart of these settings as the learner helps create the learning conditions and learning outcomes with the teacher.

One powerful example of students taking on a different role in the classroom happens when teachers use the United Nations Global Goals for Sustainable Development as a framework for inquiry. Students explore their passions, interests, and curiosities based on the 17 U.N. goals, identifying learning objectives connected to a particular goal where they'd like to focus. Teachers then co-design standards with learners, standards with language such as gaining a deeper understanding of "x" or inspiring an audience to "do y."

Students achieve a more genuine ownership over their learning as they grapple with these authentic problems -- ones that have troubled global leaders for decades. In these spaces students take on more of the heavy lifting of learning as they are actively involved in the construction of understanding.

2. The teacher as guide and mentor

Just as the role of the learner has shifted in these classrooms, so too has the role of the teacher. Teachers in these spaces are constantly reflecting and making changes in order to foster a culture of learning. They are highly aware of what's happening around them; they take the time to stop and listen; and they pick up on the slightest clues and use these to shape next steps. They constantly ask questions of themselves that guide their practice and inform their decisions. Cumulatively they use these reflections to revise their path and better meet the needs of their students.

In all of these classrooms, teachers use a variety of strategies to support their students. It's a misperception that student-centered classrooms don't include any lecturing. At times it's essential the teacher share his or her expertise with the larger group. But teachers in these classrooms also make space for learner-centered discourse such as Socratic Seminars, in which students drive the discussion and the teacher guides and facilitates the collaboration. Or students might lead a lesson with the teacher observing and compiling formative feedback to support reflection, revision and growth.

In the inquiry classroom, students often interview experts in a specific field in order to gain a deeper understanding of their inquiry topic. Teachers support them with direct instruction that introduces the class to what a strong interview entails, and identifies the processes that should be adopted to ensure students will be successful in this task. During this time exemplars are shown and discussed, sample questions are collaboratively created and planning initial steps are accomplished.

Embarking in this learning together as a group, by way of a lecture, makes sense in that all students must gain this broader and more general understanding of interviewing. The teacher then facilitates smaller breakout groups where students can delve more deeply into their individual interviews and begin to personalize the task in a more meaningful and supportive manner. It is in this gradual release of control over learning that the inquiry classroom thrives.

3. The whole child is celebrated and nurtured

Whether it be social-emotional learning, personal awareness and social responsibility, grit and growth mindset, or empathy, the language around learning has shifted in these spaces to focus on nurturing the whole student. Dispositions are at the core of these classrooms where qualities such as creativity, collaboration and communication are explicitly discussed, reflected on and supported.

In all of these classrooms there's a joint emphasis on the product or summative piece to learning as well as the process of learning. It is in this process that students demonstrate meaningful growth in the characteristics and dispositions of a lifelong learner.

This is evident in inquiry spaces that utilize the design thinking method. This process calls on students to identify a challenge, gather information, generate potential solutions, refine ideas, and test solutions. High school students in one Vancouver classroom designed a solution to bring clean drinking water to rural areas that did not have access to this essential resource in their communities.

Some students prototyped an affordable handheld water purification system, other students designed a community sewage treatment facility, and a third group created a water use plan for the community. It's worth noting that many students didn't ultimately achieve a tangible or working solution by the end of the unit. But that wasn't the goal. More important was the empathy gained during the process. The design-thinking process provided rich opportunities for student reflection and allowed the teacher to see social and emotional skills at work.

4. Structures and frameworks exist but learning isn't overly prescribed or standardized

In these classrooms, standards do not solely drive the learning and content is not overly standardized. Students are often learning about different things that they have all individually chosen, but each student is operating within a common unified structure. Learner agency is a core component of being student-centered. Teachers can use strategies and routines to help students organize, reflect and revise as they go.

This is evident in high-quality project-based learning classrooms where projects are focused on student learning goals and include essential project design elements such as identifying key understandings, posing a challenging problem, partaking in sustained inquiry, reflection, revision and sharing learning with an authentic audience.

One example of this in action is a classroom where students were learning about positive impact on others. The provocation used by the teacher was an inspiring video titled Project Daniel.

After watching the video the teacher challenged students to "help one, help many" and identify a problem, plan a solution and put this plan into action in order to make a difference in someone else's life. One group of students 3D-printed fidget spinners for younger students dealing with anxiety. Another group designed a public service announcement campaign encouraging kindness and acceptance in their school community. And another group interviewed senior citizens at a local old-age home to document, archive and share their advice for youth in order to build empathy. Although each group was working on a uniquely personalized project, they all learned from one another throughout the process as they shared their work.

Inquiry is at the heart of many education buzzwords and can be a useful tool for framing ones approach to them. John Dewey, Lev Vygotsky, Paolo Freire and Jean Piaget planted the roots of inquiry long ago, but every educator can leverage their constructivist example to find a pedagogy that best fits their unique teaching style. Ultimately the goal should always be to empower students to continue wondering and seeking their own answers.

Trevor MacKenzie is an award-winning English teacher at Oak Bay High School in Victoria, BC, Canada, who believes that it is a magical time to be an educator. He is also the author of Dive into Inquiry: Amplify Learning and Empower Student Voice, and co-author of Inquiry Mindsets: Nurturing the Dreams, Wonders, and Curiosities of Our Youngest Learners, along with Rebecca Bathurst-Hunt.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.